Being truthful, as I look back on my childhood, some of my first emotional experiences of death were fictional portrayals in media. The slaying of Bambi's father and the execution of Ol' Yeller were experiences that pre-date any real wake services I was allowed to attend, at least according to my memory. At those points in my life, if I'm honest with my self, a vague knowledge of the story of the Passion of Christ, imparted via Sunday mass and the teachings of my parents, simply didn't hit as hard.

I think I was about three when I remember accidentally seeing someone killed on a tv show. I think they had been shot, but however it was, I remember clearly thinking that it were real, and my mortified parents having to explain to me that it was an imaginary thing, and that the actor was indeed ok. As I grew older, of course there were more fictional portrayals, many treated with less care for younger sensibilities: The death of King Kong, the act of revenge in a saw mill in Walking Tall, the administration of various coups de grace by Mr. James Bond, are all stand-out movie experiences in my mind. My experiences with assigned reading in early adolescence were no doubt more meaningful: The devastating mercy-killing of Lennie in Of Mice And Men, Finny's death, preceded by a supreme act of forgiveness, in A Separate Peace. For myself, I was an avid reader of science fiction and fantasy by the time I was twelve, and even these rarely shied from portrayals of death both meaningful and incidental. I'll never forget reading The Lord of the Rings for the first time, and realizing that Tolkien, at the height of his storytelling power, had created in his fantasy world a place where death was not only re-defined metaphorically, but as a matter of the economy of his universe as well. I would wonder later if, having experienced world wars, the author had a need to ascribe additional meaning to a character death than was likely for the vast majority of the millions who died senselessly in those conflicts.

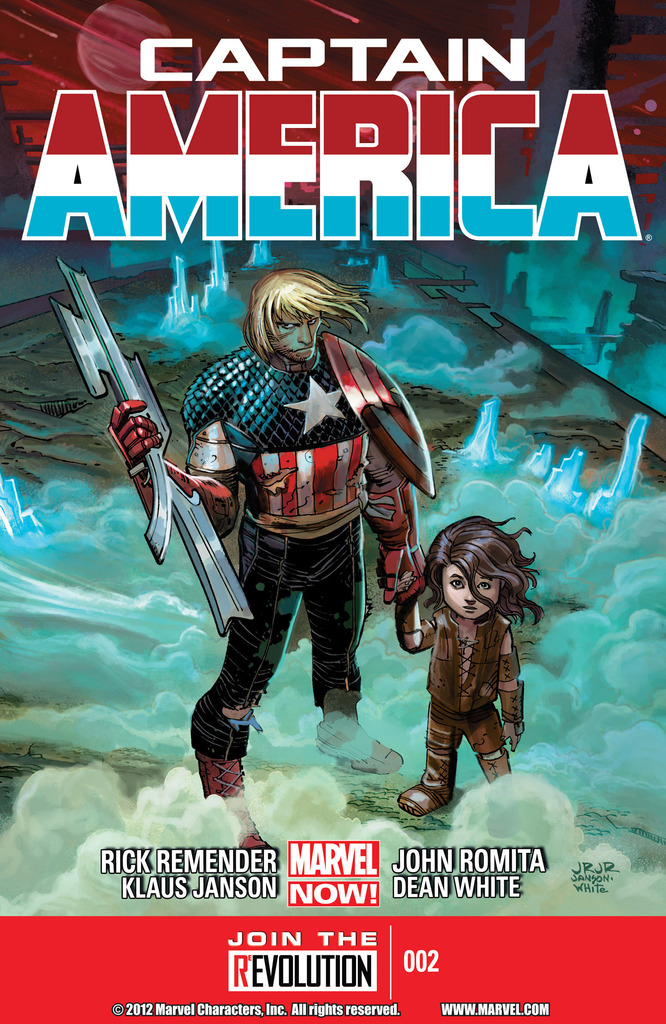

And yes, death is portrayed in comics. In fact, if one were to list the most impactful comics in recent memory, they almost to a one portray the death of some important character. Alan Moore's Watchmen, DC's first (and last) Crisis event, the Death of Superman, the assassination of Captain America, The Dark Knight Returns, the list goes on....and now, as I write this, Spider-Man is seemingly joining the ranks. But he isn't truly dead, to be sure....these super-heroes just can't stay dead, can they? Even Rorschach survives in print media after his obliteration, having wholly and completely served his character's purpose, albeit in prequel fashion in some inferior attempt to ring the registers one more time without covering any new, meaningful ground (in my humble opinion). Why is that?

Part of it, to be sure, is in their nature as characters: What is Superman, if not an icon of human virtue set loose with all our human frailties erased? We've been ascribing such abilities to gods and goddesses, to magical beings of folklore and myth and religion for thousands of years...why wouldn't illustrated fiction create a character with abilities "far beyond those of mortal men"? And why wouldn't such a character survive through the decades? What is Batman, but a timeless representation of human need for justice and order amidst the deadly chaos of lawlessness? A character who, in every respect, represents the pinnacle of human aspiration....the perfect detective, the most knowledgeable of consultants, the most capable martial artist, the richest of businessmen, the most prepared to defeat evil. His connection to his parents (really, the only thing distinctly human about him), and their death, represents a life-debt owed him by criminality that can never be paid, despite his unceasing efforts to collect, and connects us to the character in ways as old as civilization. We've all experienced loss, we all have a need for order, we all fear lawlessness but are occasionally subject to circumstances that don't demonstrate care for the well-being of ourselves or our loved ones. Who wouldn't want to read about a character who, although human, ceaselessly prepares for the worst, who stays at the pinnacle of physical prowess, whose mental faculties are forever keen, who stands as a bulwark of order in the darkness...who, after remaining in his thirties for 75 years, give or take, is human AND immortal? The cardinal sin in the latest cinematic portrayal of the character, for many fans, was that Batman demonstrated human frailty: He wasn't prepared. His detective skills weren't perfect. He aged, he lost, and eventually, having experienced both fundamental loss and fleeting moments of triumph, he stopped.

And what is Spider-Man, but an iconic portrayal of the responsibility of those entrusted with great power? Of the human need, even in the face of time's unrelenting march forward, to attempt to re-set the clock with actions that, however heroic, cannot affect the failings of the past? The character, no matter how many punches he delivers, can't change the story of how his uncle was killed, and what he could have done to prevent it. We, the readers, can see the futile nature of this conflict with things already past. Strange, then, that some of those same readers purporting to "love" the character of Peter Parker, and who indubitably "get" the nature of his heroism at odds with a past he can't change, seem to balk at the seeming end of his story....as if the ending of that story could invalidate fifty years of storytelling...as if his humanity (you know, the humanity Marvel became a household name for giving their characters in the first place) and mortality were the absolute worst thing a writer could illustrate. To me, the events of the last issue of Amazing are fitting: The character is demonstrated as mortal, but in death, he sets one of his greatest enemies on a path to heroism that continues. His heroic act, at the last, ensures the continuation of his crusade, and stamps his legacy on his world well past his own "sell-by" date.

These stories all start from places literature had trod for thousands of years prior, and will likely go on with for that much more. The question is not from whence they come, but rather, as characters, where they're capable of going: How fully realized can a character be at some frozen state of development? How many times can we open the cover to find them on the same mission, motivated by the same compulsion, at the same age, with only slight tweaks to the nature of their nemeses to clue us in to the fact that this story could be any different from those that came before it? How many times must any changes to the status quo be redacted to please nostalgia, to assuage reader insecurities in the face of an uncertain future, to give them the dependable, static portrayal of their fantasies before any semblance of truth or lasting meaning bounces off the literary wall like bullets off the iconic "S"? True, there are those works in comics where these paragons seemingly experience loss, are hurt, come to new realizations about themselves, enter into new relationships, etc. Those are all character arcs, right? But can they stick? Do they ever change things in some fundamental way? And if they do not do so, where is the meaning, and how can there be real progress?

What is the cost, then, of such faithfulness to iconography? Superman, for example, purports to be a beacon of hope to the masses, an example for us to follow...but how can the character realize this, either literally or within the fiction, unless humanity is left in some way changed by his presence? The seeming fact is that neither real fans nor the fictional Metropolis can deal with a world without a Superman. Instead, it appears they're stuck in some sort of nostalgic time-loop that's dependent on he being there, unchanged, for next month's episode. In a character where any lasting change to him, or to the fictional landscape that hosts him, is forbidden, there can be no real character arc, can there? Forbidding lasting change, forbidding death itself, preserves the character for future generations...or does it? Do those stories all disappear if the character dies? And if we keep him alive and unchanged, how is there hope that the story has meaning beyond what it had fifty years ago?

Some would explain that there is a conservationist value in the everlasting icon itself, that its immortality parallels for us some unceasing battle that mankind must fight against the darkness, and I'll admit there is some literary value in this. But there is a reality that concerns me at work here: We of this earth are mortal. We crave things with staying power, things that deny aging, and the idea that our existence is memorable in some way. We don't want our stories to end. But eventually, end they will, and we can immortalize ourselves only by creating lasting change, whether through our works or our human progeny. To be sure, I'd like for my daughter to enjoy the works of fantasy and fiction her father enjoyed on life's journey, but I would hope that her generation is able to create their own such works to surpass those that came before. I wonder to what extent we, the aging fan base of comics, have put boundaries around what will come after with our demand for dependability in the characters we love. I love the medium of comics as a concept, but I question whether the endeavor is served, after 75 years or so, by an aging fan base laying the yoke of their iconic, unchanging characters around the necks of so many of their brightest young writing and artistic talents. How much paper is enough to devote to these characters? How much of the industry's resources must revolve around them? How much of our young talent should be devoted to a re-treatment the essentials of which haven't changed in decades? And how much storytelling opportunity is wasted by denying ourselves the two words most essential to all our childhood fables:

The End.